Excerpt from the Digital Violence platform (https://www.digitalviolence.or)

Opinion piece by Jean-Philippe Commeignes, Commercial Director @Tixeo

Europe, struck by the war in Ukraine for nearly two years, has been experiencing an intensification of the terrorist threat for several weeks following the outbreak of war between Israel and Hamas. In this extremely tense geopolitical context, the statement by the Minister of the Interior in a recent interview about access to data and encrypted messaging conversations has put back on the table the binary question of balancing privacy protection and the need for security.

The fundamental issue is not so much the debate on the unlikely negotiation of access to public encrypted messaging, but the strict control of the use, sale, and export of cutting-edge surveillance technologies. These technologies, beyond circumventing the encryption problem, represent a dangerous temptation within the European Union, as highlighted by Sophie in ‘t Veld, a Member of the European Parliament, in her latest opinion piece on the risks of this industry.

Global War on Terror and Mass Surveillance

After September 11 and the launch of the war on terror by the USA and its allies, the demand for surveillance and intelligence solutions exploded. A 2017 Privacy International report counts several hundred companies in this sector created between 2001-2013, 75% of which are from NATO countries. The approach, tinged with American techno-solutionism to address the threat, led to the implementation of mass surveillance programs revealed by whistleblower Edward Snowden in 2013, then employed by the famous NSA agency. This also revealed the role of major American platforms in this data collection.

Uncontrolled Changes in the Post-Snowden World

These revelations had two major effects:

• The gradual generalization of encryption, even in consumer solutions, making authorities more “blind” in technical collection, and prompting states to have means of circumvention;

• The tightening of data protection regulations, through the General Data Protection Regulation, positioning Europe as a standard-bearer for privacy protection worldwide.

Concurrently, the rapid adoption of smartphones, messaging, and social networks facilitated the coordination of social movements like the Arab Spring, creating a stronger demand from authoritarian countries for solutions to contain them.

“The Cyber Surveillance Industry Has Adapted Across the Entire Value Chain”

The cyber surveillance industry has adapted across the entire value chain to meet both domestic and export markets, in a mix of business and foreign policy. It’s a market with layers.

The first is the research and acquisition of unknown computer vulnerabilities to publishers, called 0-day, which allow those who hold them to compromise targeted software and equipment without user action (0-click). The second is spy software that uses these vulnerabilities as invisible vectors to deploy their real-time surveillance tools.

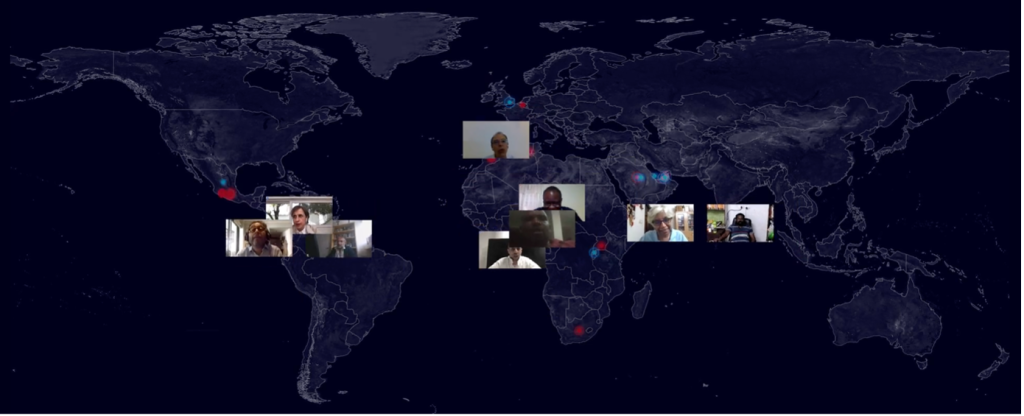

This was highlighted twice thanks to the work of journalist consortia and NGOs like Amnesty International. The first time in July 2021 by Forbidden Stories and 17 media outlets as part of the Pegasus Project, named after the spyware developed by Israeli company NSO. The second time, a month ago, in the context of the Predator Files, named after another type of software, this time developed by a consortium of companies based in Europe, particularly in France, Intellexa. This is emblematic of an ecosystem still adrift and used for political purposes. The Digital Violence platform, developed by Forensic Architecture, allows for a frightening but salutary immersion.

Today, the cyber surveillance industry market is estimated at $12 billion according to the director of the Citizen Lab.

The PEGA Commission and Its Recommendations Against Illiberal Temptations in Europe

The work of the Parliamentary Commission on Spyware, called PEGA, following the Pegasus scandal, has highlighted the main problems within the European Union.

Domestically

First, domestically, with the confirmation that 14 European countries and 22 security agencies had acquired this type of software and that 5 member countries had used it against civil society in disregard of the law and institutions. This underlines that even our democracies can be seduced by tools that bypass the indispensable control for legitimate and proportionate use, sometimes relying on a very broad definition of the concept of national security.

Internationally

Internationally, they showed the limitations of the EU’s export rules for these technologies, both permissive and without homogeneous application within member states. This allows for the implementation of opaque company structures to take advantage of these weaknesses for easier export.

A recent report by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace indicates that EU member states granted 317 export authorizations in this segment between 2015 and 2017, compared to only 14 refusals. It also indicates that these exports are primarily to countries where human rights are secondary.

This is Europe’s paradox: being a model promoting democracy and human rights protection while importing and exporting, without strict control, the means of its regression.